February 21, 2023

Jake Blount's Genre-queer Afrofuturist Folk Music

Brian Bromberger READ TIME: 7 MIN.

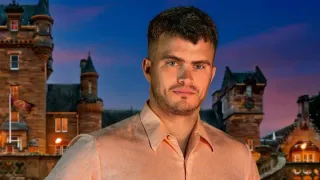

If you ever listened to Jake Blount's (pronounced Blunt) music, it defies description, making it unforgettable. He describes his style as "playing fiddle and banjo from Black and Native American musicians, mostly in the Southeastern United States."

Being African American and gay, based in Providence, he dislikes the 'old-time' designation because it basically referred to white musicians for white people.

He commented in an interview with editor Rachel Cholst of Country Queer, "A lot of Black people who were playing the same music were written out of the story because they weren't considered marketable. For me the term 'old time' is this racist fabrication of what the musical landscape of the South really was. And I don't view old-time, blues, gospel, and bluegrass as being these neatly separable categories. It's really about different ways of voicing some of the same musical and lyrical themes that you find throughout all these genres."

Blount framed his own style as "genrequeer," meaning it transcends categorization and any one style. Listening to his albums shatters any preconceptions you might have about the typical string band sound.

His backing band is queer and gender-balanced. He notes the majority of Black, old-time musicians he knows are queer, which has an impact on the music created. Blount has met "some opposition by white musicians and folklorists due to his progressive interpretations of traditions," but observed that at the Clifftop Bluegrass Festival in 2021, all the winners, including himself, were queer, and many were People Of Color, meaning a momentous change in this genre is occurring.

In an interview with "What's Up Newport," he explained, "I think it's exciting to see the embrace of people like me in all different parts of that industry. I've had the opportunity to be on the board of this awesome organization called Bluegrass Pride. We're doing a ton of work to provide more visibility and opportunities for LGBTQ artists in the Bluegrass scene and make it clear that other folks are welcome to join... and starting to work more in the old-time circles where being queer has been more accepted for a longer period of time."

Openly Queer

For Blount, identifying queerness in musical history is paramount. "When it comes to queer musicians prior to the past 40 years, no one was out. So there are queer musicians all over the place, but we don't know who they are. That's part of the reason why I put a song from one of the 1920s blues queens on my 'Spider Tales' album – because they were openly queer, a lot of them, but were never open about it, or everyone knew – but it's a weird situation where people can sort of capitalize off their queerness, without ever owning it publicly. So then it's not officially part of the narrative."

Blount, 27, described in an interview with Decolonizing the Music Room what led him to music.

"So, not when Trayvon Martin was killed, but when George Zimmerman got let off the hook for it – when the grand jury decided they would not indict him – I was at my mom's parent's house in Maine. I went up into the attic and downloaded these books of slave songs and spirituals on my Kindle and decided I was going to look through them and see how my ancestors were dealing with it historically."

In his acclaimed debut album, "Spider Tales" (which made multiple Best of 2020 lists), Blount was reclaiming his rural roots by "profiling the collective rage, grief, and defiance of his ancestors... and demands for justice and resentment that I see simmering in the black traditional music canon throughout history."

In the CD's press release, Blount observed, "There's a long history of expressions of pain in the African-American tradition. Often those things couldn't be stated outright. If you said the wrong thing to the wrong person back then you could die from it, but the anger and the desire for justice are still there, just hidden. The songs deal with intense emotion but couch it in a love song or in religious imagery so it wasn't something you could be called out about. These ideas survived because people in power weren't perceiving the messages, but they're there if you know where to look."

However, in his latest CD, "The New Faith," released by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, Blount envisions Black American religious music in a dystopian future devastated by thermonuclear warfare and anthropogenic climate cataclysm. The record is based on field recordings of Black religious services from the early-to-mid-20th century, but composed entirely of new arrangements and subtle rewrites of traditional Black folk songs, especially plumbing the depths of spirituals (i.e. Bessie James' "Take Me To the Water," Jim Williams' "The Downward Road," Mahalia Jackson's "Didn't It Rain," Fannie Lou Hamer's "City Called Heaven,") and original compositions by Blount.

Reconciled Faith

In the liner notes, he wrote, "I only rarely attended church as a child, declared myself an atheist at the tender age of eight, and developed a strong antipathy toward Christianity when I began to understand my queerness, since they aren't super-welcoming to people like me. In moments of homesickness, sorrow, and fear, they're the songs I turn to for solace.

"While I've never reconciled fully with Christianity, I have come to appreciate the Black Church and its music for secular functions... as a social venue, a political organization, and a mutual aid fund. Despite its flaws, it has borne us safely through the long years of a dark history... the songs they handed down to us are their first-person accounts, veiled in allegory and symbolism. Black folk music is one of the strongest connections between present-day Black people and our lost ancestors; so that studying it broke me of my atheism."

Blount composed the music in the first months of COVID-19 and just after the murder of George Floyd. Isolated from friends and family plus recovering from a bout of long COVID, he comments, "I was consumed with fear, stricken by the concreteness of my own mortality and the collapse of everyday life. I ended up asking two questions: What will this music sound like when I'm dead? What will this music sound like when everyone is dead?"

This roots music concept album incorporating an Afrofuturist vision (based on the sci-fi writings of Black lesbian Octavia Butler) occurs in the aftermath of the near-annihilation of civilization, with descendants of U.S. Black refugees confined to an island camp off the coast of New England.

Most of the songs are re-created lost music from memory using acoustic instruments (guitar, banjo, bass, fiddle), though there are elements of unsettling electric guitar with a harsh, high-pitched droning tone mostly for special effects, as well as looping and digital processing with percussion, layered harmonies, rap, hip-hop, gospel, and falsetto-inflected disco, including spoken moments of recitation by Blount as preacher and prophet like a musical call-and-response.

Not interested in making happy music, he instead manages to elicit anger, grief, and trauma (i.e. slavery, Jim Crow, police brutality) about what we've done to the planet with uplifting themes of hope and resilience that, despite a grave, uncertain future, something of us will yet survive.

Blount's music is the personification of Black spirituality embracing humanism, queer liberation, science fiction, and religious belief. It's clear from his work that Blount is as much a storyteller, historian, and activist as a musician, which is why "New Faith" is both thrilling and disconcerting. It's essential listening for anyone trying to make sense of our world dealing with racism, homo/transphobia, and environmental catastrophe. He not only updates traditional string band music, but opens new vistas and audiences for its future.

www.jakeblount.com

Help keep the Bay Area Reporter going in these tough times. To support local, independent, LGBTQ journalism, consider becoming a BAR member.