October 4, 2022

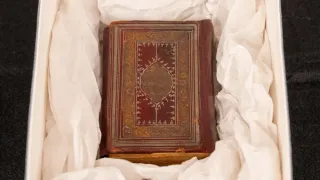

Julian Aguon's 'No Country for Eight-Spot Butterflies'

Mark William Norby READ TIME: 4 MIN.

I knew very little of the Chomorro people who populate Guam until reading "No Country for Eight-Spot Butterflies" (Astra House, New York 2022) by queer Indigenous writer and human rights lawyer Julian Aguon. The largest of the islands of Micronesia, Guam is located about 1,500 miles south of Japan and has been a United States colony since 1898.

The United States Department of Defense maintains a military presence in Guam to support and defend its interests in the western Pacific Ocean. Currently in the process of relocating 5,000 Marines from Okinawa, Japan to Guam, the addition of a 59-acre multipurpose machine-gun range will be built 100 feet from the last remaining reproductive håyon lågu tree in Guam.

That's one of the endangered species currently in danger in Guam where, for example, the yo'åmte, or native healers who perpetuate Chamorro traditional healing practices, are experiencing the added endangerment to native plants used for medicines to treat everything from anxiety to arthritis.

"No Country for Eight-Spot Butterflies" is part memoir and part manifesto. The writing is deeply interested in what ultimately is a question of human survival, and in preserving and respecting minority cultures so we can at the same time respect the earth and its geographical regions and micro-cultures of the larger human species.

For our purposes in queer journalism, we research and write on queer identity and the challenges we face therein. But "No Country for Eight Spot Butterflies'' has larger lessons for us to learn. As much as I love this book, I had to look further into LGBTQ Indigenous identity outside of its pages.

Typically called "Two-Spirit" by non-Indigenous people, Two Spirit is a question of gender, not of sexual orientation. Most indigenous communities around the world have specific tribal terms for sexual and gender fluid members, and naturally they differ from Indigenous language to language.

Indigenous tribes embraced gender fluidity prior to colonization, and many Indigenous tribes recognize at least four genders: Feminine female, masculine female, feminine male, and masculine male. In terms of identity and the Indigenous, there exists here opportunity for non-Indigenous queer people to choose. That is, the opportunity to address gender roles and orientation/reorientation and to step into one's identity anew.

Chamorro people have traditionally accepted LGBTQ tribal members, and homosexuality has never been prohibited.

From there, I decided to engage in an interview with Aguon, and asked him questions that generated a further sense of our collective responsibility, queer or non-queer, Indigenous or non-Indigenous.

Mark William Norby: Why should LGBTQ individuals be interested in "No Country for Eight-Spot Butterflies?"

The book is, at least in part, a coming-of-age story that traces my journey as a queer, Indigenous boy growing up on the island of Guam, illuminating how my broader set of intellectual and political commitments (i.e., global justice activism) are rooted in and informed by that upbringing.

How do LGBTQ identity, de-colonialism, and environmental justice intersect?

Queer people are particularly well-suited to understanding intersectionality, so much so that the book doesn't address this pedagogically or even explicitly; it takes it for granted. I think that's an important point. We shouldn't always be in the business of explaining ourselves. Part of what I love about this book is that it seeks to crash every party at once. It isn't neatly categorizable, and that's work we queer people have been doing since day one. And to your question, there are simply no silos anymore. Silos, like borders, are over.

What are the current social conditions of Two-Spirit Chamorro individuals in Guam and Micronesia, and what is the most important issue in their struggle for respect and equality in the civic communities of the island nations and/or "colonies" of Micronesia?

The people of Guam, generally speaking, are incredibly warm and loving people. You might say we welcome first and judge [on merits] later. The same is true for queer members of the community, however they happen to define themselves.

Guam is a special place in that way; large extended families, or clans, are still strong. They are the fabric of our society. And most of my friends have families who accept them without question. Of course, that is not the case for everyone. I'm painting with a broad brush here, but this has definitely been my experience and that of many of my closest friends.

What can U.S. LGBTQ mainlanders do to help Guam in the struggle for environmental justice?

They can start foregrounding Guam in their conversations about empire; about militarism, colonization, and climate change. Guam is by definition a colony. And it's a colony that is also a frontline community when it comes both to the escalating threats of militarization and the adverse effects of climate change. Despite this, we are but a blip on the national radar. We are hardly ever considered, let alone discussed.

Aguon and I ended our interview, and I realized how profound, heart-moving, and alluring the arguments are in addressing not only Chamorro identity and climate change, but also the different ways of seeing and engaging our world and in the process, of saving it.

www.astrapublishinghouse.com

www.julianaguon.com

Help keep the Bay Area Reporter going in these tough times. To support local, independent, LGBTQ journalism, consider becoming a BAR member.