December 31, 2016

Young HIVers Work to Combat Stigma

Brian Bromberger READ TIME: 10 MIN.

When young men seroconvert, one of the main factors they must contend with is stigma.

The stigma and shame of being HIV-positive can deter men from even getting tested for HIV, fearing negative social consequences. Even when diagnosed as HIV-positive, some men worry about discrimination and don't seek good health care. Studies have shown increased rates of depression, lower self-esteem, anxiety, social isolation, substance abuse, alcoholism, even romantic loneliness for young HIV-positive men.

Many men don't want to disclose their serostatus to friends and family, thus cutting themselves off from supportive social relationships just when they need them most. To explore the ramifications of this discrimination, the Bay Area Reporter spoke to three young gay HIV-positive men.

Keisuke Lee-Miyaki, 33, is a minister at the Buddhist Church of San Francisco and has volunteered at Positive Force, a client service of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation.

Armando Estrada, 25, is a treatment and health educator for Clinica Esperanza, part of the Mission Neighborhood Health Center, focusing on undocumented immigrants.

Chris Richey, 31, is director of marketing and communications for SFAF.

As if to reveal the commanding power of stigma, it took months to find these three men willing to be interviewed for this article.

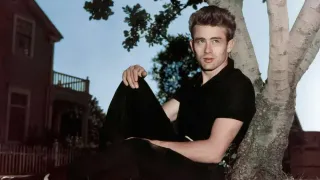

Keisuke Lee-Miyaki. Photo: Brian Bromberger

Stigma a worldwide issue

Lee-Miyaki found out in Japan in September 2012 that he was positive. He was shocked.

"I had a bias against HIV, as in Japan HIV is stigmatized and not talked about publicly, nor is being gay," he said. "I thought only heavily sexually active people got the disease. I thought I was going to die as I didn't know about the protease inhibitor drugs."

He had been working as a minister in the biggest Buddhist congregation in Japan, but figured he would probably be fired if word got out. Needing a vacation in a "new world," he came to the U.S.

"I was only going to stay three months. I didn't want my family to know that I was HIV-positive," Lee-Miyaki said. "When I had told my mother I was gay, she cried and said she was hopeful I would be cured of this mental disease. My ex-boyfriend suggested I go to UCSF as it was the best medical treatment center for HIV."

Estrada, originally from Mexico, was living in Los Angeles when he tested positive in November 2014.

"There were times I didn't use condoms ... you party, you get drunk, but it is pointless to reflect on who or where I got it. I have it now, so what will I do next?" he said. "At first I thought I could never have kids and would die young. So I sensed right away I needed more information."

Ventura County officials linked him with someone already living with HIV, who showed him the ropes. He got involved with the Being Alive support group, "where I learned the reality of what living with HIV is, as there is lots of misinformation and half assumptions."

Richey was diagnosed in 2010 in L.A. after graduating from college, having moved there from East Texas, at the same time his mother was diagnosed with Stage 4 lymphoma (she is now cancer free). Richey is well acquainted with stigma.

"Stigma is the number one barrier to ending the epidemic. It impacts every facet of the HIV caring continuum," he said. "It prevents people from going to get tested, because they are afraid of the label, afraid they will never have sex again, or afraid they are going to die. Stigma impacts on people living with HIV because they have to take a pill every day, which becomes a reminder they are HIV-positive. Stigma never really goes away and it never will go away until we say it is OK to have HIV."

Lee-Miyaki said he has not experienced any discrimination here being HIV-positive, but he discriminated against himself.

"I didn't want to identify as HIV-positive," he said. "I didn't tell anyone. I still had a strong bias and was afraid people wouldn't accept me. By telling other people I was HIV-positive, I would be reminding myself I was HIV-positive. I projected my bias to other people. And I still had that cultural norm of Japan not to talk about HIV in public."

Getting a referral from a licensed social worker at UCSF, he went to Positive Force, a community of HIV-positive men. A doctor diagnosed him as depressed and he joined a peer counseling group there, learning how to manage the physical and emotional sides of HIV.

Estrada said that he has experienced discrimination.

"I was waiting at a clinic in Ventura and this guy started talking to me. 'Who are you waiting for?' he asked. I told him my HIV case manager. And he said, 'I can't believe you have it. You look so smart. It's always the pretty ones that get you. Did he tell you he loved you?' I was in shock but it motivated me to get more educated," he said.

Similar to Lee-Miyaki, it took him about seven months "to get back into circulation." He experienced much rejection on Grindr, with responses like, "I don't play with Pos people."

"I would go on dates disclosing my status and giving them accurate information," Estrada said. "But it didn't change their minds, because it was coming from someone who has HIV and they figured I was just trying to get into their pants so he'll say whatever he wants to say. Yes, I felt bad, especially if it was someone I was really interested in, but at the end of the day it's about getting informed. I planted a seed and it is up to them to pick it up."

For Richey, like Lee-Miyaki, the worst stigma he experienced was internalizing the shame he felt.

"I was living halfway across the country from where my mother and family live. I was ashamed that I was a self-fulfilling prophecy," he said. "I grew up in the Bible Belt where being gay was already bad. I came out of the closet in a blaze of glory at age 16 in a small town. I was constantly told I would get AIDS and die. And then I went off and I got HIV. I just proved all those bigots right. My mother was fighting cancer and she didn't ask for that. I felt HIV was my fault. I got lost in drugs for a while and then I tried to kill myself. I carried all that shame that comes from being poor and gay in the South. Fortunately good friends got me the help I needed and my family was always supportive."

Chris Richey. Photo: Brian Bromberger

Some progress made

While, 35 years after the start of the AIDS epidemic, there is still stigma, Richey feels some progress has been made. In fact the city's Getting to Zero initiative includes ending HIV stigma by 2020.

He marvels how well people with HIV in San Francisco are taken care of, compared to Texas, where it is much harder for an HIV-positive person to hook up casually.

"The Texas Legislature just passed abstinence-only education instead of sex education or more HIV funding," Richey said. "These trends continue in the South and here we are subsidizing federal funding for HIV care and the results speak for themselves.

"The stigma is compounded exponentially by all these other factors, yet San Francisco is a beacon of hope compared to the rest of the country," he added. "HIV is now classified as a chronic, manageable condition, but so is diabetes and diabetics are not looked at in the same way people living with HIV are. Why? HIV is an infectious disease impacting people of color, people who are gay, people who inject drugs. Until the conversation changes, until we can say that people are OK and it's not bad to get HIV. We all have sex. Mistakes can happen and there is this judgment made on someone living with HIV and that has to change."

Support group

Estrada started volunteering at Clinica Esperanza in the Mission where he learned about the Spanish Shanti Life support group.

"I built up a strong community as I had wanted a support group for Latino men," he said. "I was undocumented then so I felt I would get more understanding from someone that was going through the same thing as me. The clinic welcomes everyone regardless of citizenship status."

Estrada wanted more information before he told his family as initially he was scared to reveal his status. Last Christmas he returned to Mexico to tell his brother and sister, so in case something happened, they could speak to his mother rather than doctors. Two months later he informed his mother.

"I posted a speech I gave at last year's World AIDS Day on Facebook. Family members told my father, who read it and he has been very supportive. I have been very fortunate," said Estrada.

Involvement with support groups has made him confident and not scared, even comfortable to share his status with other people.

"HIV doesn't define who I am, even though it is part of me. If I get any negative reaction, it is by people I wouldn't want in my life anyway. There's more to you than your status, despite what other people say."

A year ago a position at the clinic opened up for a treatment and health educator and Estrada was hired.

"You get to see people experiencing HIV in different ways and educate them," he said. "There is much misinformation in Latin America about HIV with much stigma and a subject you don't talk about."

For Richey, the best way to deal with stigma is to find support groups like Fifty-Plus or Black Brothers Esteem, both programs of SFAF.

"Stigma wins when it isolates you from others, when it keeps you from going to the doctor, or missing appointments, or having relationships with other people, these are all things that keep you going and make you healthy," he said.

In 2012, Richey was a co-founder of the Stigma Project, a nonprofit organization that seeks to end HIV stigma through art, provocation, awareness, and education.

"We use social media and new media to conduct social marketing campaigns. We've had a lot of success with Facebook campaigns, educational campaigns with Gilead, and work on HIV criminalization. We did the first PrEP campaign. We used shame to get Paris Hilton to apologize when she made that homophobic and derogatory statement that most homosexual men probably have AIDS in a taxi that was recorded by the driver.

"All these comments, such as UB Clean 2, angered me years ago, but now everything is more normalized like people that work in emergency hospital rooms get used to death and now that I work in this HIV field, they aren't as raw for me. Because of my work for the Stigma Project, I secured my position at SFAF," said Richey.

Richey said the Stigma Project is on hold for now.

Estrada is not afraid of the stigma. However, he recognizes that stigma affects everything, even appearance.

"I had a client who took half a pill because he thought it would be enough to help him and wouldn't affect how he looked," Estrada said. "There's lots of drug use in the gay community, so you are having a three-day orgy fest, just smoking Tina and having sex, when will you take your HIV pill and if you are dating someone that doesn't know your status, you spend the night but avoid taking your pill so he won't ask any questions.

"I ask people about their beliefs concerning HIV and I say, let's look at the facts. I had another client who was homeless and said he couldn't take his medication but he mentioned that he always took his shoes off at night and the first thing he does when he wakes up is that he puts on his shoes, so I suggested putting his bottle of pills in his shoes so it would remind him to take them in the morning, and it worked."

Estrada said his clients are frightened by the election of Republican Donald Trump, especially since many are undocumented and worry about being deported.

"They leave their countries because they are gay and come here to be safe, yet read about someone who is racist, misogynist, and unpredictable and no longer feel safe," he said. "They worry about being attacked in the street because they don't speak English. Trump has emboldened people to say things they previously may have thought, especially about immigrants, but would not have voiced publicly."

Richey has very strong feelings about PrEP and its effect on the LGBT community.

"When it was first approved in 2012, it was stigmatized and people were slut-shamed for using it," he said. "PrEP has done a lot to highlight this divide in the gay community among people that weren't as comfortable in their own sex as they thought they were. Now I feel there is a sexual revolution in our community again.

"Before, when people were finger-wagging you better wear a condom, Mark King wrote a great piece, 'Your Mother Liked It Bareback.' It's true and nobody finger-wags the straight community. PrEP has enabled us to have this intimacy that is different than before and that is remarkable. You are not in charge of that condom because in the heat of the moment you have no control. So what PrEP says is, 'I'm going to take that pill in the morning before I go out,' so six hours ago your prevention already started," Richey said.

Lee-Miyaki has made enormous strides. He started studying English at City College, as well as health education. He became involved with the Asian and Pacific Islander Wellness Center. Feeling guilty about being HIV-positive for almost a year after coming to San Francisco, he wasn't interested in meeting men. When he did meet men online, he wouldn't disclose his status until he actually met them in person. He later met an employee at Positive Force, TJ Lee-Miyaki, also HIV-positive, and they are now married.

"Last year, I appeared on a poster for Positive Force hung on bus stops all over the city," he said. "I had to accept myself before I could accept others with HIV. My husband's being an openly positive gay man inspired me to have no shame or bias. TJ thinks I would be a great resource for gay Asian people and Positive Force has suggested a role for me as an advocate for them also, but I need more language skills for that."