October 26, 2015

Experimenter

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 5 MIN.

Imagine that someone in authority orders you to inflict pain and suffering on someone else. Do you do it? Do you refuse? Do you weigh the costs of defiance -- your own pain, in other words -- against the ordeal the victim will endure, and formulate your response accordingly? Or do you follow basic, hard-wired instincts -- for protection, say, or for self-preservation, or for deference to authority?

How would you know without being put into that position? Theory is fine, but real-world testing is the basis of science, and that's what the aptly-named "Experimenter" is all about.

Dr. Stanley Milgram, a psychologist who studied what he termed "social relations," tested volunteers by putting them into that situation. To do so, Milgram engaged in a level of legerdemain that led some to question the ethics of his methods: He had a person in the know pose as the "learner" in an experiment in which a "teacher" would punish incorrect answers to multiple-choice questions with increasingly severe electrical shocks. What the research subjects didn't know was that the shocks weren't real, and neither, therefore, were the yelps and pleas coming from the adjacent room, where the "learner" was supposedly sitting wired up to an electrode.

The point of the experiment was to determine whether most people would obey instructions and continue to administer what they believed to be painful shocks, and how far they would go. Would some, most, or all of the so-called "teachers" continue to deliver more and more painful jolts, all the way to the end of the series of ten questions? Professional opinion before Milgram conducted his experiments was that only one in one in a thousand people would be that callous, or that cowed by the authority figure in the room -- a polite, but insistent man in a lab coat who would meet questions with the firm instruction that the experiment had to continue, no matter what, all the way to the end.

Milgram's results were strikingly different that the intuitive opinion of his peers. He found that 65% of the "teachers" carried out all ten questions, hitting the switch to activate the electrical charge with each incorrect response (including a lack of response which some "teachers" feared indicated incapacity, or even death, on the part of the "learner"). The "teachers" did this even though they were clearly distressed at having to carry on inflicting what they thought to be harm.

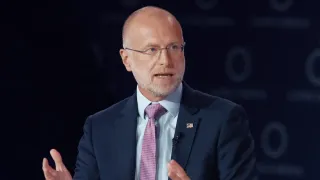

What can we learn from this? Another question is, why do we need to know about such aspects of human behavior? Writer-director Michael Almereyda brings Milgram's work to the cinema screen with a certain careful -- even tentative -- style, but his point is never less than glaringly overt. When the Jewish Milgram (Peter Sarsgaard) addresses the camera in a diary-style narration to explain that his interest in the results stems from a wish to understand the atrocities of the Nazi holocaust -- a systematic eradication of millions of human lives, carried out by a literal army of genocidal participants -- he does so while striding up a corridor. Behind him, massive and silent, and unremarked by passers-by, lumbers an elephant. (The animal makes its return later, when Milgram makes an ironic reference to George Orwell's dystopian novel "1984," characterizing it as a story set in "a totalitarian world where people aren't very good at thinking for themselves.")

That elephant is both too much literalism, and just enough of a fantastical flourish. Almereyda cushions his audience from the issue's difficulties and thorny, disquieting nature by inserting any number of blatantly fake and contrived touches -- glaringly obvious rear projection, sets that are half illustration, Milgram's ongoing narrations, extras toting copies of "1984" and another Orwell book, "Animal Farm." These choices create a distance between narrative and viewer and make it clear that this is a movie that wants us to remember that it's a move, even if it's based on fact.

It's an approach that yields mixed results. The entire film has a stilted quality about it, and yet that fits wrote Milgram's character; his affect is so detached and bloodless that when he announces Kennedy's assassination to his class, the students think he's lying to them to see how they'll respond.

This film reminds one of other period pieces with scientists and at their center, most notable the AMC seres "Masters of Sex." As happened with Milgram, Masters found his work subjected to moral outrage and academic scorn; and yet, what Masters and Johnson discovered about human sexuality -- as uncomfortable as it made some people -- has remained of seminal importance. The same is true of Milgram's work. As Milgram's character notes -- from a posthumous perspective -- his work continues to draw heated rebuttal, and yet human affairs are punctuated with periodic, and eminently predictable, outbursts of mass, organized violence.

All this leads to another, equally important question: When it comes to sex and violence, why are human beings so reluctant to learn the essential truths about their own individual and social psychologies? The film seems to offer some understanding toward this reluctance; Milgram says that we might be "puppets," but we are "puppets with perception," and the fact that we can acknowledge this could conceivably give us the strength and presence of mind to depart from the script that it seems nature has hard-wired into us.

As cinematic expression, "The Experimenter" works well; it's innovative and challenging and even exciting. But as a movie, it's often unapproachable and sometimes irritating. As with "Master of Sex" (and "The Imitation Game," and "The Theory of Everything") both scientist and scientific inquiry intersect with romantic attachment; Milgram is in the midst of his initial research at Yale when he meets Sasha (Winona Ryder), whom he marries. (Somehow she puts up with his slightly clinical demeanor, in much the same way Johnson puts up with Masters' high-handed persona in "Masters of Sex," and she even joins him in his work, not unlike Johnson in that series.) The film's analytic view of humanity carries through at every turn, but it lacks a certain sort of human attachment.

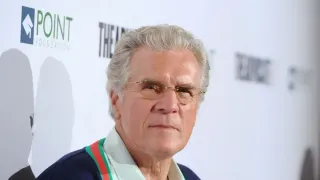

That's not to say there aren't fun, even humorous, passages, though these too are slightly off-kilter. In one scene, his research having been fictionalized for a "Playhouse 90" episode starring William Shatner (Kellan Lutz) and Ossie Davis (Dennis Haysbert), Milgram pays a visit to the set, where he has an odd (but enlightening) conversation with the two stars about what his work says about racism. (Lutz as Shatner is even less believable than the use of rear projection to complete sets and portray cars driving through landscapes; his accent is decidedly non-Canadian, and his overplaying, coupled with the fact he's wearing a yellow shirt, is a distractingly big wink).

Why stick with this movie? It's more than the human vulnerability to group-think and social conformity. The material is fascinating, and the direction, though not always successful, is inventive. Sarsgaard plays Milgram absolutely straight, and if he's a strange one, well, this movie proves above all else that all of us are far from perfect.