Apr 25

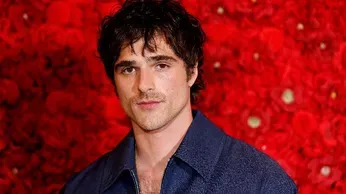

In Two Current Releases, Jacob Elordi Likes It Both Ways

READ TIME: 8 MIN.

Of the current crop of rising Hollywood stars, Jacob Elordi continues to carve his own path with indie and mainstream projects that push the cultural envelope. He didn't start that way: his breakout role was in the by-the-numbers Netflix comedy "The Kissing Booth," but it make him a tween idol. Then after making two sequels, he turned to the more adult and complicated content, such as playing Nate on HBO's "Euphoria." Next came a co-starring role opposite Ben Affleck and Ana de Armas in the psychological thriller "Deep Water," and critical acclaim and a BAFTA nomination in Emerald Ferrell's twisted "Saltburn."

At 6'5", it is easy to imagine the strikingly handsome 26-year old Aussie would command any room he is in; and he has put his good looks to use in fashion campaigns for Bottega Veneta, Calvin Klein, Hugo Boss, TAG Heuer, and Chanel No.5. Those good looks and his brooding manner have led to him being compared to such 1950s icons as Montgomery Clift and James Dean, most notably in fashion campaigns where he's smoking a cigarette and dressed in a t-shirt and leather jacket. This likely led him to be cast in such period pieces as "Priscilla," where he played Elvis Presley; or the younger Richard Gere in the flashback sequences of "Oh, Canada." But what he does so effectively is bring a contemporary vibe that is fearless and special – qualities that bring to mind the young Paul Newman. It would be easy to imagine Elordi in a remake of "Hud," except this time he'd be playing around with the older woman and a hot ranch hand.

This weekend may be a good time for an Elordi Binge as two of his most recent projects went into release. First Daniel Minahan's film "On Swift Horses," which is in a limited theatrical release and on VOD; and the five-part Aussie miniseries "The Narrow Road to the Deep North" that is streaming on Amazon Prime. And seen together, he shows how comfortable he is portraying both queer and straight sex.

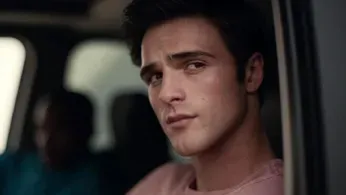

"On Swift Horses" is an adaptation of Shannon Pufahl's 2019 novel set in the early 1950s that follows Julius, a Korean War vet, who visits his brother Lee (Wil Poulter) and wife Muriel (Daisy Edgar-Jones) when discharged. There's immediate chemistry between Julius and Muriul, but nothing is as it seems in this sprawling tale that leads to Julius resettling in Las Vegas where he takes up with Henry ("Babylon's" Diego Calva), a co-worker in a casino where they work, for steamy sexual relationship.

Talking to Vanity Fair, Elordi mentioned how how he turned to Newman's movies for inspiration. "I tried to build a voice around the way that he spoke, and movement around the way he moved–particularly in 'Hud,' because he has a great sensitivity in his steely output there." He also felt prepared for the period vibe coming to the film after making "Priscilla." "It was helpful because a lot of the prep for that film was historically the same, and the things that Elvis brought into the world were happening parallel to the times of ['On Swift Horses']. And I'd spent a lot of time in Vegas as well."

Nor has mentioning such 1950s icons as Newman and Elvis escaped critics when writing about Elordi. In her review of "On Swift Horses." New York Times critic Alissa Wilkinson compares "On Swift Horses" to the 1950s melodrama "Giant," and writes that its two stars Daisy Edgar-Jones and Jacob Elordi "embody a certain languid old-school movie star quality, the kind that makes you want to get up close and just look at them as they look at someone else."

She continues: "Elordi in particular moves his body like he dropped into our time from an earlier era, which might be why, despite his rise to fame having originated from roles in the very contemporary 'Kissing Booth' movies and the HBO show 'Euphoria,' he keeps showing up in movies set in the past. He's Elvis Presley in 'Priscilla,' for instance; in 'Oh, Canada' he plays the young version of Richard Gere's character, in an uncanny imitation of Gere's energy roughly circa 1970. That quality is hard to describe, exactly, but you know it when you see it, and here you certainly see it."

One of the big questions about the film is how did Elordi and Calva prepare for their intimate scenes?

"He's a real cool customer," Elordi said of Calva to Vanity Fair. "We had a week of intensive [prep] in the motel room, and Dan gave us a lot of freedom to run around and to play and to find that love within those four walls."

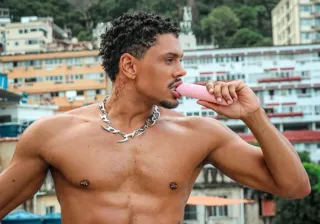

"Believe me, being naked around Jacob Elordi is intimidating!" Calva told Instinct Magazine in their current cover story. "He's like a god – he's too perfect! It's hard not to do a hot scene with Jacob shirtless!"

Calva says that motel room was a sanctuary for the two men. "When they're inside the hotel room, in their own world, because they have to hide from the actual world – they're kids," Calva said. "It's like when you fall in love for the first time when you're eight. You fall in love with your cousin or your teacher. Something really sweet, platonic, in a way."

And Calva was quick to point out that the nudity and sex scenes were handled with care to convey the love between the two characters that Minahan (their director) took from the novel.

"[Minahan] told us, 'I don't want to provoke the audience. This is about actual love,'" Calva revealed. "He didn't want the classic story of tragedy around queer characters, followed by kinky sex scenes. These are two sweet guys who really fall in love."

To which Elrodi agreed. ""It's a sprawling, epic, nongeneric love story–and I think that theme is entirely universal for every single person on the planet."

Source: Mr. Man

But "On Swift Horses," which is in theaters and available for streaming, isn't the only project that the ever-busy Elordi is turning up in this week. He has the lead role in the the five part mini-series "The Narrow Road to the Deep North" that is available for streaming on Amazon Prime Video in the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. He is also filming the long-delayed third season of "Euphoria," but that won't be aired until sometime next year.

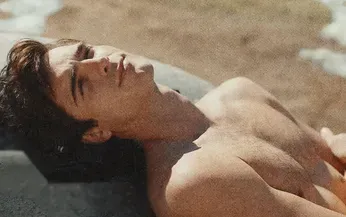

In "The Narrow Road to the Deep North," the 26-year old hunk plays Australian army surgeon Dorrigo Evans as a young man before and during the Second World War. In the happier pre-war sequences, Elordi has a steamy affair with his uncle's wife (Odessa Young), graphically displayed in scenes that has the actor displaying his butt four times.

But during the War sequences, Elordi is a POW in in a Japanese camp where he and his comrades are subjected to grueling physical hardship.

"The preparations for the PoW scenes were grueling, requiring more than just emaciated bodies. The reality of forced hard labour coupled with starvation meant Narrow Road's PoW survivors had to be skin and sinew," reports The Guardian.

"The cast undertook a medically supervised six-week boot camp in rainforest south of Sydney to achieve the effect. Elordi says the on-screen camaraderie mirrors the close relationships the actors formed while shedding weight over that time."

"'We were all in it together, so there was this great overwhelming amount of love in the whole process,' says the actor.

"'It was incredibly challenging but deeply necessary, of course ... because nobody wanted to phone that in or make a mockery of it."

But as grim as the story is, the mini-series captures the dark humor of Richard Flanagan's Booker Award-winning novel "The Narrow Road to the Deep North" through the ironically-named character of Tiny Middleton, a large, physically imposing man who during a sanctioned prisoner variety show is encouraged to show off his enormous penis to his fellow students, even waving in the grinning Elordi's face. In another scene Tiny stands on impressive attention when he gets a raging hard-on while sleeping, reports The Sword.